Color printing was a major step forward for making art and literature more popular. From the cave paintings of prehistoric Europe to scribing on parchment in Ancient Greece, color printing has evolved and developed over time.

In this blog, we’ll take a look back and over color printing history and explore how we have got the sophistication and impressive quality we see today.

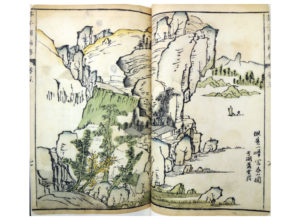

Traditional East Asian method of printing text and images involved woodblock printing, similar to woodcut technique in the West. The technique of printing a number of colors by using multiple blocks, where each block is inked in a different color, was known from early on.

China

The earliest remaining woodblock print fragments are from China and are silk-printed with three-colored flowers from the Han dynasty (before 220 AD). Clearly, woodblock printing developed in Asia several centuries before Europe and the Chinese were the first to use the process to print solid text.

Michael Sullivan, a British art historian, writes that

“The earliest color printing known in China, and indeed in the whole world, is a two-color frontispiece to a Buddhist sutra scroll, dated 1346”.

Color prints were also used later in the Ming Dynasty. Early color woodcuts mostly occurred in luxury books, notable examples for which are Ming-era Chinese painter Hu Zhengyan’s Treatise on the Paintings and Writings of the Ten Bamboo Studio of 1633, and the Manual of the Mustard Seed Garden published in 1679 and 1701, and printed in five colors.

Japan

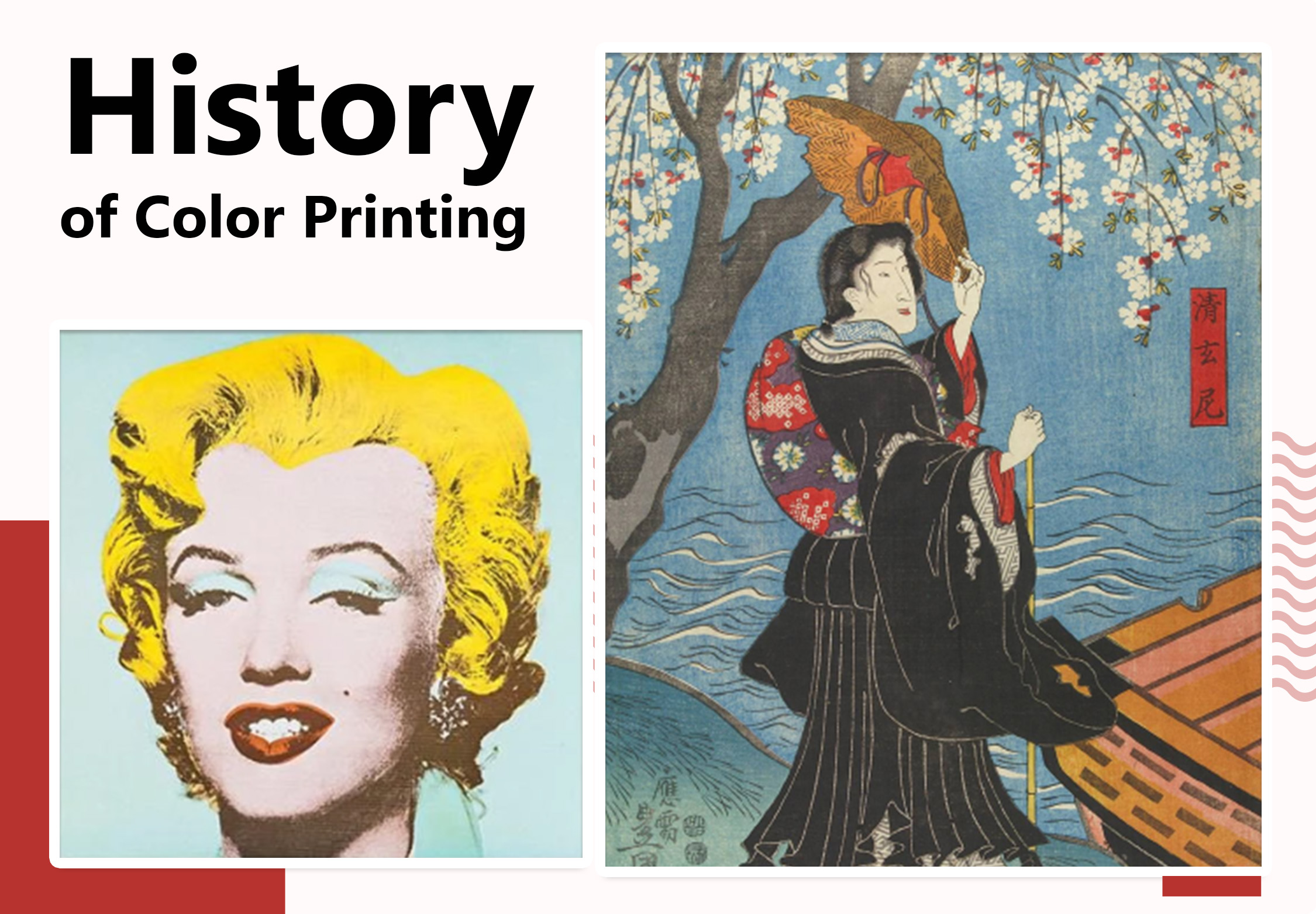

Earlier, most prints had been in black-and-white, colored by hand, or colored with the addition of one- or two-color blocks. In 1670s, Ukiyo-e, a genre of Japanese art flourished. Its artists produced woodblock prints and paintings of such subjects as female beauties; kabuki actors and sumo wrestlers; scenes from history and folk tales; travel scenes and landscapes; flora and fauna; and erotica. (Source: Wikipedia)

However, color prints were only used for special commissions at first. In 1760, Nishiki-e, a Japanese multi-colored woodblock printing technique was invented. This technique is used primarily in ukiyo-e, and was used widely for sheet prints from the 1760s on.

As printing was done by hand, printers were able to achieve effects impractical with machines, such as the blending or gradation of colors on the printing block.

The text was mostly monochrome and many books continued to be published in black-and-white illustrations sumizuri-e. But with the growing popularity of Ukiyo-e, the demand for more colors and complex techniques also increased. By the 19th century, most artists designed prints to be published in color. Major stages of this development are:

Sumizuri-e (“ink printed pictures”) – monochrome printing using only black ink

Tan-e – monochrome sumizuri-e prints with hand coloring; distinguished by use of orange highlights using a red pigment called tan

Beni-e (“red pictures”) – monochrome sumizuri-e prints with hand coloring; distinguished by use of red ink details or highlights.

Urushi-e – a method in which glue was used to thicken the ink, emboldening the image; gold, mica and other substances were often used to enhance the image further. This technique was often used in combination with hand coloring. Urushi-e can also refer to paintings using lacquer instead of paint; lacquer was very rarely if ever used on prints.

Benizuri-e – images printed in two or three colors, usually containing red and green pigments, as well as black ink. This printing technique is often confused with “beni-e”, above.

Nishiki-e – A Nishiki-e print is created by carving a separate woodblock for every color and using them in stepwise fashion. Registration marks called kentō were used to ensure correspondence between the application of each block.

In the 18th century, artists started to hand color their woodblock prints. However, hand coloring was labor intensive and time consuming. That’s when some printers took the matter in their hands and developed kento registration system. It allowed them to align one color with another in printing, accurately. But this technique was also limited to one or two colors. By the end of 18th century, artists started merging many different colors in the design. Black ink used charcoal as its pigment whereas the other colorants were vegetable-based dyes and were color resistant. The colors used were considered to be more subdued compared to the vibrant colors used by Western artists.

Between 1820-1830, the trade with Europe began, providing Japanese artists the access to new and more durable pigments. However, in the late 1800s, Lithography replaced the majority of traditional printing in Japan.

Europe

Unlike in Asia and the Middle East, papermaking reached Europe only in the 12th century. Textile woodblock prints preceded printing on paper, and it was common to use different blocks to create color patterns. The earliest way to add color to items printed on paper was to apply ink by hand. It was widely used for images printed in both Europe and East Asia. This method is used on Chinese woodcuts since 13th century, followed and practiced at a very skilled level by Europeans in the 15th century, until elements of the official British Ordnance Survey maps were hand-colored by boys until 1875.

Gutenberg Revolution

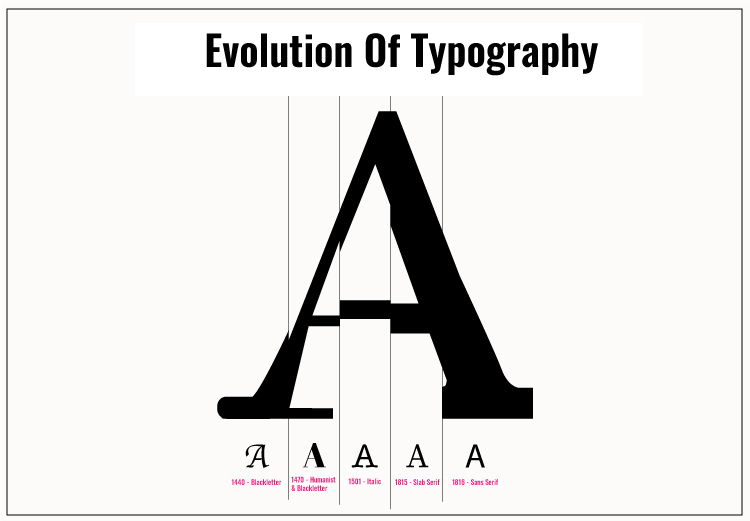

In the mid 15th century, Johannes Gutenberg transformed printing in Europe by introducing mass-producing mechanical movable type printing. ‘The Gutenberg Bible’ was the first among his publications. It was a two-color (red and black) bible written in Latin that is now considered one of the most valuable books in the world. By the end of the 15th century, printing was established in more than 250 cities in Europe.

Innovation and Growth

Throughout the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, the European printing industry grew and developed, affecting more and more people in society. New technologies and products continued to emerge. In the 17th century, Isaac Newton discovered that all colors result from the combination of three primary colors: green, red, and blue. However, the primary colors he discovered are related to the behavior of direct light. But in 1710, the German painter and sculptor Jacob Christoph Le Blon, inspired from Newton’s old idea, became the first to produce color print images by superimposing layers of colors.

This technique has evolved into the famous four-color system, still in use today, using magenta, cyan, yellow and black to create accents. This may sound simple, but there are at least two major challenges. First, color separation: involves splitting the image into different layers. This was done by eye until the end of the 19th century. Second, registration: involves placing different colors in the right place on the paper. This was a daunting task when printing used damp paper which expanded with moisture.

Then, in 1790, Alois Senefelder invented the printing technique of lithography – a technology that ultimately helped push forth the Gutenberg press into the modern era by using the chemical properties of oil and water to create the first flat-surface printing press.

In 1837, the French printer Godefroy Engelmann started to experiment with multicolor lithography and invented the process of chromolithography. He studied the colors of original art pieces and used a printer to separate them into a series of print plates. These panels were individually applied to a piece of paper. And soon, color printing became a part of everyday life.

While Engelmann was developing the chromolithography, a French engineer named Louis Jerome Perot found a way to achieve similar success in textiles. His machine “perrotine” for printing colors on cloth ultimately influenced the global textile industry. In addition, printers were able to print not only colored paper and cloth, but also glass, leather, ceramics, metals, plastics, wood and all sorts of objects.

And things were further refined by combining the concept of lithography with the concept of photography to create a process called photolithography.

As the process improved, it often became faster, more sophisticated, and easier to use. In short, printing technology, once ignored by publishers such as newspapers and magazines, became quite common.

The last manual aspect of crafting began to disappear with the advent of photography. Before photography, artists and designers had to create an image directly on the surface of the stone or metal to print. After, they used photographs to transfer the image to the printing surface.

In addition, photographic filters can be used to automatically separate colors.

In 1843, botanist Anna Atkins published the first book consisting of nothing but photographs when she published Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions, a book that took advantage of the photographic properties of contact printing to capture the details of British seaweed on a printed page.

In 1893, illustrator William Kurtz patented the first color-separation technique that uses a combination of three separate plates—cyan, magenta, and yellow—to cover the array of colors. The technique was improved in 1906 when the Eagle Printing Ink Company introduced the four-color wet ink process, based around the CMYK color set. (CMYK stands for cyan, magenta, yellow, and “key”—also known as black.)

In 1894, Joseph Pulitzer acquired a color printing press for The New York World, allowing his first-of-its-kind comics page, The World’s Funny Side, to run as a full supplement on Sundays, complete with elaborately colored illustrations

Offset printing also made it possible to transfer the images to cylinders made of rubber or other materials. This was the beginning of rotary press, capable of printing at high speed on a wide range of papers. Full color magazines such as Fortune and National Geographic also entered the popular culture. However, daily newspapers remained black and white for a long time for cost and efficiency reasons. But eventually, they also joined the world of color in the 1980s.

Andy Warhol’s series of colorful portraits of Marilyn Monroe is the best expression of today’s color printing: mass production of splashy images of all kinds. Warhol primarily used stencil-like printing technique, but his work reflects the technological advances of his time. The name of the famous photocopying machine company comes from xerography, a technique that uses an electrostatic field to concentrate pigment particles in a desired area and fixes them through heat.

Since the 1980s, the outbreak of information technology has made it possible to create shapes and designs using computer software. Inkjet printers turn these electronic instructions into dots on paper by directing a small stream of ink from a nozzle, like a spray gun. Laser printers project a laser beam onto a cylinder, creating a difference in electric charge that attracts ink. The ink is later transferred from the cylinder to the paper.

In the 1990s, digital printers were introduced by companies like HP, Canon, and Xerox. Toners (dry inks) were applied using a xerographic (electromagnetic) process that fused the toners to the paper. The results from the first machines were pretty sloppy, but today’s digital presses produce beautiful color that can’t be distinguished from conventional offset print.