“Printing is the most beautiful gift from heaven. It soon will change the countenance of the universe…” – Louis-Sebástien Mercier

The phrase “Knowledge is power” has never been truer than with the advent of the printing press. While Johannes Gutenberg is often credited with this groundbreaking 15th-century invention, it’s worth noting that he wasn’t the first to automate book production. Long before Gutenberg, the Chinese had developed woodblock printing in the 9th century, and Koreans were using movable metal type.

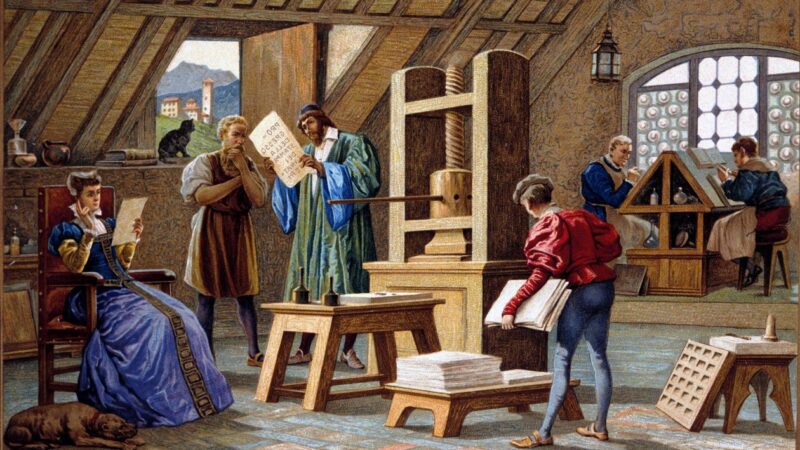

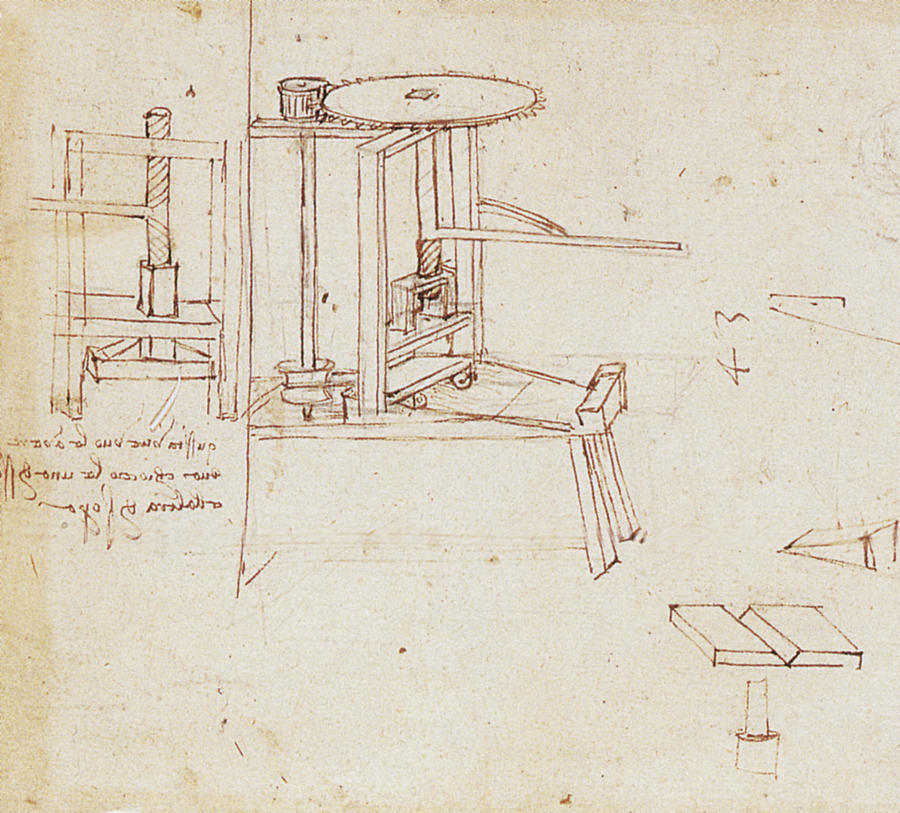

So, what set Gutenberg’s press apart? Historians often highlight his innovative use of a screw-type wine press to apply even pressure to inked metal type. This seemingly simple modification enabled mass production, drastically reducing the cost of books and making revolutionary ideas and ancient wisdom accessible to a rapidly growing literate population.

But how did this “machine” truly revolutionize the world? Here are some of the most significant impacts:

From Local News to a Global Network

Gutenberg’s journey wasn’t one of fame and fortune. His most notable achievement was the first print run of the Bible in Latin, a monumental task that took three years to produce around 200 copies – a remarkable speed compared to hand-copying!

Video showing how Gutenberg’s press works

Gutenberg’s ambitious print run of 200 Bibles highlighted a significant challenge: distributing these books to readers for in his town, only a few individuals could read Latin. Thus, the bulk of the copies needed to be circulated in other areas.

Unfortunately, Gutenberg died penniless, with his printing presses seized. However, other German printers saw the potential and moved to Venice, a bustling center of Mediterranean trade in the late 15th century. Venice’s strategic location and extensive trade networks made it a hotbed for printing.

Printers in Venice produced four-page news pamphlets, selling them to sailors. When ships reached distant ports, local printers would copy these pamphlets and distribute them widely. This created a new thirst for knowledge, as communities gathered in public spaces to hear paid readers share the latest news, from gossip to war reports. This radically changed the consumption of news, making it a daily habit.

Renaissance 2.0: How Printing Supercharged a Cultural Rebirth

The Italian Renaissance, characterized by a renewed interest in classical art and literature, began before Gutenberg’s printing press. 14th-century political leaders in Italian city-states aimed to revive the Ancient Roman educational system that had nurtured giants like Caesar, Cicero, and Seneca.

Sketch of a printing press taken from a notebook by Leonardo Da Vinci.

A key focus of this early Renaissance was finding long-lost works by figures like Plato and Aristotle and bringing them back into circulation. Wealthy patrons funded expeditions to remote monasteries, and Italian emissaries spent years in the Ottoman Empire learning Ancient Greek and Arabic to translate and copy these rare texts into Latin. However, this process was arduous and expensive, limiting access to the wealthy elite.

For instance, a single hand-copied book in the 14th century could cost as much as a house, and libraries were a luxury few could afford. By the 1490s, with Venice as the printing capital of Europe, a printed copy of a significant work by Cicero cost a schoolteacher only a month’s salary. This shift made knowledge affordable and allowed culture to be shared on an unprecedented scale.

Martin Luther: The First Best Seller

German religious reformer Martin Luther is famous for revolutionizing Christianity. His success was partly due to the power of mass media. Luther wasn’t the first to challenge the Church, but thanks to the printing press, he became the first to widely publish his message. Previous “heretics” were quickly silenced by Church authorities, but the timing of Luther’s rebellion against the selling of indulgences coincided with the proliferation of printing presses across Europe.

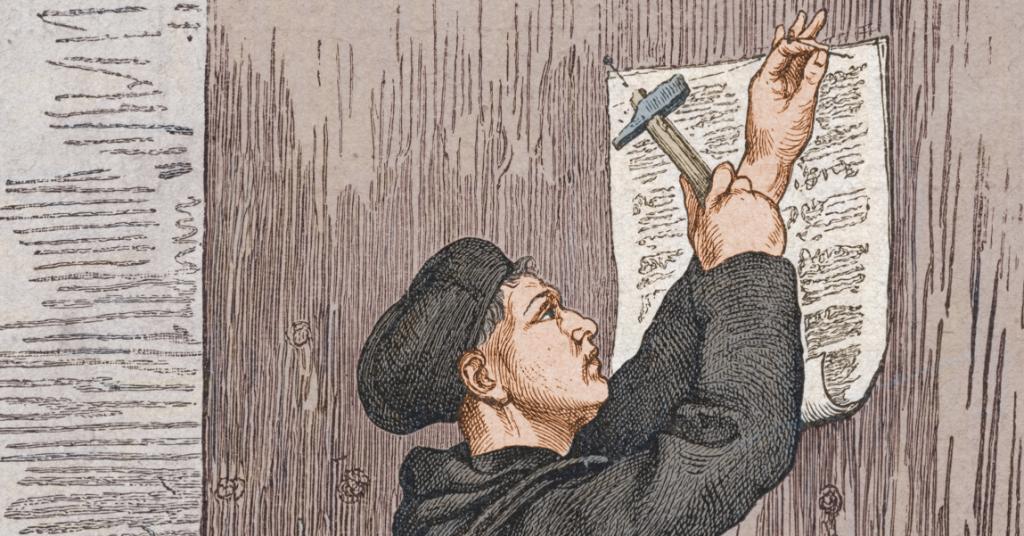

Martin Luther nailing his 95 theses on the door of Wittenberg castle church.

According to legend, Luther nailed his “95 Theses” to the church door in Wittenberg on October 31, 1517. Within seventeen days, printed copies of Luther’s document were circulating as far away as London. The printing press, combined with the power of his message, made Luther the world’s first best-selling author. His translation of the New Testament into German sold 5,000 copies in just two weeks, and from 1518 to 1525, Luther’s writings accounted for a third of all books sold in Germany. His German Bible went through more than 430 editions.

Empowering the Scientific Revolution

The English philosopher Francis Bacon, a key figure in the development of the scientific method, identified the printing press as one of the three inventions that fundamentally changed the world. For centuries, science had been largely a solitary pursuit. Scholars were often separated by geography, language, and the slow, error-prone process of hand-copying texts.

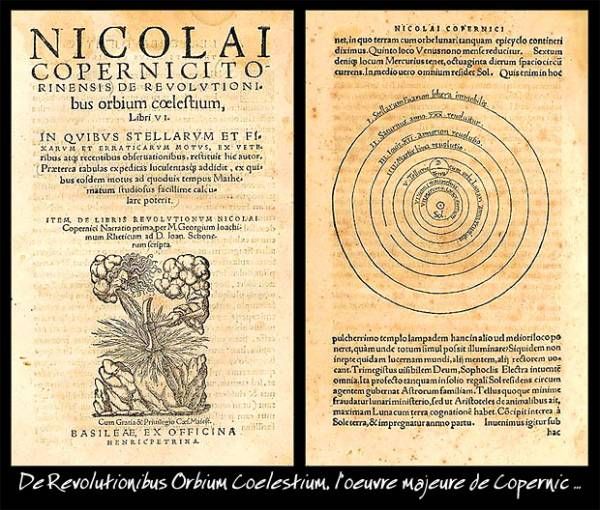

Polish astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus’ pioneering text “De revolutionibus orbium caelestium” (On the revolution of heavenly spheres), 1543, which represents his complete work.

The printing press changed all of that by enabling scientists to share their findings and experimental data with unprecedented accuracy and speed. The real magic of the printing press for science wasn’t just the speed of dissemination, but the reliability of the information itself. Scientists could trust the printed data and focus on making new discoveries.

From Public Opinion to Revolution

During the Enlightenment, philosophers like John Locke, Voltaire, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau gained a wide readership. The printing press played a vital role in spreading revolutionary ideas and a new focus on individual freedom.

Louis-Sebástien Mercier, writing in pre-Revolution France, recognized the transformative power of the printing press.

He declared: “A great and momentous revolution in our ideas has taken place within the last thirty years. Public opinion has now become a preponderant power in Europe, one that cannot be resisted… one may hope that enlightened ideas will bring about the greatest good on Earth and that tyrants of all kinds will tremble before the universal cry that echoes everywhere, awakening Europe from its slumbers.”

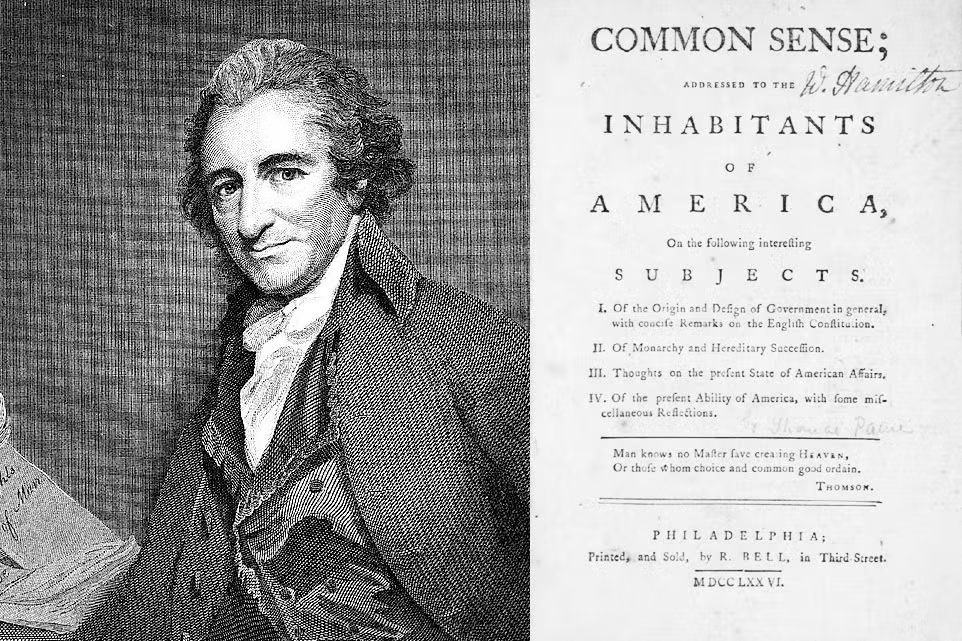

Thomas Paine’s “Common Sense” was printed in 1776.

Even those who couldn’t read were impacted by these revolutionary ideas. When Thomas Paine published “Common Sense” in 1776, despite a literacy rate of only 15% in the American colonies, more copies of the pamphlet were printed and sold than there were people living in the colonies! This proves how information can spread even to those who can’t directly access it.

Final Word

The printing press was not just an invention; it was a catalyst for transformation that reshaped societies, economies, and cultures. By making knowledge accessible to the masses, it sparked revolutions in science, religion, and politics, and laid the foundation for the modern world. At the same time, it symbolizes that the significance of innovation lies not just in the technology itself, but in its ability to empower humanity and drive progress.

We at Machine Dalal have a wide selection of print, packaging and converting machines listed with us. Industry sellers from all over the world list their print equipment with us to reach interested buyers who regularly visit our platform to find equipment that matches their needs.

Contact us to know more or simply download our app onto your Android or iOS smartphone.